RSS Mixer, a recently released as an “alpha”, lets you create an account, input one or more RSS feeds, and gives you a combined output. Once you’ve set up an account (using OpenID or a one-off account at the site), entering feeds to mix is straightforward. The user interface is available in eight languages (there’s a language link in the site’s footer). Choices include German, English, Spanish, French, Russian, and Chinese.

Mixed feeds can be tagged and shared — there are built-in widgets for mobile versions, creating web widgets, emailing a mixed feed to a friend, and exporting a mix as an OPML file, in addition to the version viewable on the RSS Mixer site — for example, an ego search for RSS4Lib.

One thing I noticed is that sorting in mixes is odd. In the above two-feed mix (comprised of RSS4Lib’s RSS feed and a Technorati search feed for “rss4lib”), an RSS4Lib entry is sometimes followed by one or more posts discovered by Technorati about that particular entry. Other times, the Technorati post comes first. In all cases, though, the RSS4Lib entry was posted before anyone could comment on it — sorting should be consistent, whatever the algorithm is.

By further mashing up RSS Mixer’s output, it is possible to create a keyword search across multiple specific feeds. FeedSifter (reviewed here in July 2008) lets you searching a feed for one or more keywords. As a test of this, I used RSS Mixer to create a combined feed out of about 55 RSS- and library-related feeds. I then used FeedSifter to limit that to anything in that mixed feed that mentions metadata.

It would not surprise me if searching were on the drawing board for a future version of RSS Mixer, but there’s no indication of this functionality now.

Google Chrome and RSS

I’ve just started playing with Google Chrome, Google’s new browser. Its strengths are impressive, but I was disappointed to see no support, as yet, for reading RSS feeds. They display as text, with all tags stripped out, and no semblance of readability. As an example, here’s RSS4Lib’s RSS 2.0 feed:

Given that Google already has a way to display RSS feeds on a web page, it seems odd to me that it didn’t make its way into the first public beta of Chrome. Even the iPhone version of Safari (which similarly does not include a built-in RSS reader) redirects RSS feeds to a web page, hosted by Apple, that renders the feed as an HTML page. For an example that only works from an iPhone (or if you can set your browser’s user-agent string to “iPhone”) see Apple’s rendering of the RSS4Lib feed.

I’m hopeful that a forthcoming release of Chrome will include some capability to read display RSS feeds within the browser.

Update, 16 December 2008. Google Chrome came out of beta on December 11, 2008, without RSS support. See Google Chrome: Out of Beta, Still No RSS.

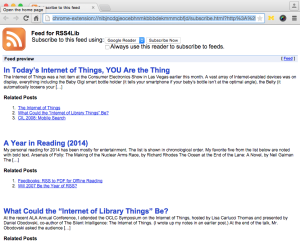

Update, 30 April 2015. At some point along the development path, Google Chrome learned to handle RSS feeds, as illustrated here:

Putting a Creative Commons License in Your Feeds

Did you know you that it’s easy to add a creative commons license to your RSS and Atom feeds — not just to your blog’s web site? Here are brief instructions for adding your Creative Commons license to RSS and Atom feeds:

RSS 2.0

You need to make two small edits to the RSS 2.0 template your blog software uses.

- Change the line that reads <rss version = "2.0"> to <rss version="2.0" xmlns:creativeCommons="http://backend.userland.com/creativeCommonsRssModule">. This is probably the second line in the RSS file. The addition of the “xmlns…” bit sets up the second item you’ll edit, pointing to the web page that defines an extension to the standard RSS 2.0 field set.

- Then add the URL to the Creative Commons license you’ve selected at the Creative Commons web site. This bit goes anywhere between the <channel> and the </channel> tags. For example, RSS4Lib has an “attribution non-commercial” license, version 3.0. So I’ve added this code to my RSS feed: <creativeCommons:license>http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/</creativeCommons:license>

Atom

It is even easier to add a Creative Commons license to an Atom feed. There’s just one line to add to the Atom template. For RSS4Lib, this is: <link rel="license" type="application/rdf+xml" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/rdf" />. Again, this assumes you’ve picked an “attribution non-commercial” license. Whatever the Creative Commons license URL, add “rdf” to the end. And that’s it.

So What?

I suppose that putting the license on the web site alone is enough, from a strict legal standpoint. However, as we all know, RSS feeds have a habit of wandering off almost on their own power. Adding the license to the feeds themselves gives you an extra bit of protection — the consumer of the feed cannot say they were unaware the content was licensed.

Creative Commons and Blogging

Copyright and RSS frequently appear to be ill-suited bedfellows. On one side we have the author’s desire to have one’s content distributed as widely as possible. On the other, we have the publisher’s desire to control the way one’s content is used — out of the concern for losing control over one’s work, perceived or real financial loss, or simple desire to be properly attributed. Where in traditional media, publisher and author are usually different (and the most common place those two roles intersected was the vanity press), in “new media,” the same person frequently takes on both roles.

Copyright is often seen as complicated, and for good reason. In the United States, anyway, a work is copyrighted at the moment it is created and may not be reproduced with explicit permission. (The legal concept of “Fair use,” in the United States, is at best murky. It’s a right that does not readily extend to other legal domains. And, it almost certainly does not apply to the wholesale reproduction of items from an RSS feed. But I’m no lawyer.) At the other extreme, the author can explicitly waive copyright — a choice that few authors or publishers would opt for. In the middle ground is licensing the use of content for various uses. This is the sensible middle ground, for most bloggers: some uses of my content are fine while others are not.

However, the challenge arises in setting the language of that license and defining the kinds of use to allow. Doing so in a legally defensible way is complicated (again, I’m no lawyer). So what should the blogger to do? Use Creative Commons. Creative Commons (CC) is a non-profit foundation that has written legally valid and clearly understandable licenses that anyone may use. By applying one of CC’s licenses to blog content, the blogger can state clearly what uses of that content are allowed. Can it be reused wholesale? Reused only if the person using it does not make any money from it? Reused only if attribution is given and no changes are made to the original? There are many permutations. (Unfortunately, there’s no standard way to license content in an RSS feed.)

RSS4Lib is now licensed under an Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States license. (Look toward the bottom of the sidebar.)

If you want to learn more about using content — including RSS4Lib — that has a Creative Commons license, I highly recommend CC HowTo #1: How to Attribute a Creative Commons licensed work at my colleague Molly Kleinman’s blog. The first in her planned series of posts is excellent, and I look forward to future installments.

Read RSS in Your Language

In the category of being so obvious it’s a wonder it took this long for someone to do it (with a subcategory of “D’oh! I wish I’d done it first”) is Mloovi. Mloovi takes a web page or an RSS feed, runs it through Google’s translation tool, and gives you a permalink for the translated output. Mloovi also gets my vote for best Web 2.0 site subtitle: “beta (if it ain’t beta it ain’t web 2.0)”. I think I’ll adopt that as my personal motto.

So, if you’ve been dying to read RSS4Lib in French, Russian, Arabic, or Hindi, here’s your opportunity. (Mloovi offers translations between any pair of these languages: Arabic, Bulgarian, Chinese (both Simplified and Traditional), Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hindi, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Spanish, and Swedish.

This tool will be very handy for me to keep up with the biblioblogging world that doesn’t happen to write in a language that I can read. I can also see it useful as a way to get publishers’ notifications, etc., where they are offered via RSS but inconveniently not in the language that the bibliographer speaks. Having permanent URLs for the translation, whether for a web page or a feed, is exceptionally handy. The feeds, I should note, have advertisements added as new items, noted with “ADVERT” as a prefix.

Mloovi also offers an iframe widget code; however, it only allows a single translation, not a choice for your users — unless you want to clutter up your interface with lots of buttons. Here, as an example, is the English-to-German translation of RSS4Lib’s feed:

Oh, and a note about the name: “mloovi” (actually, “mlooví,” with a long “í” — something impossible to render in a domain name) is the Czech 3rd person singular — he, she, or it speaks.

Addendum (12 August 08): Mike from mloovi.com pointed out in the comments that multiple languages can be selected in the widget — for example:

Bloglines Succumbs to Advertising

It was just a matter of time, but Bloglines has added advertisements to their site. When I went to read my feeds this morning, there was an ad for T-Mobile right on the starting page:

I’ve long wondered just where Bloglines was getting revenue to support itself — it didn’t make sense to me that IAC Search & Media, its owner, was keeping Bloglines running to make my blogreading life easier. So far, I haven’t noticed advertisements on individual post or folder pages. Could those be far behind?

Interestingly, the advertisement I was shown was managed by…. DoubleClick. Which Google acquired in March 2008. Now, it seems, whether you use Google Reader or Bloglines, you’re putting advertising dollars into the Big G’s pocket.

RSS: The Shipping Container of the Internet

Not too long ago, I read a fascinating book about international shipping. No, I’m serious: Marc Levinson’s The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger, published in 2006 (which happens to have been the 50th anniversary of that ubiquitous part of the global economy, the shipping container).

In a nutshell, the standardized shipping container revolutionized international trade by vastly speeding up the loading and unloading of ships. The cargo that had been brought to the wharf, unloaded from a truck into a pile on the dock, moved piece by piece into cargo netting to be hoisted by crane into the hold of a ship, so that it could be removed from the cargo net and then shoved in the corner of a hold, was now as complicated as building a stack of bricks. OK, a bit more complicated, since loading and unloading containers is really an art, the ship needs to be properly balanced, and so forth — but basically, a crane operator and few others can load a ship. Turnaround times at pier — when large, expensive, freighters were just sitting there — were reduced dramatically.

What does this have to do with RSS? Quite a bit, actually. RSS is the box into which any old thing can be packed, for uniform shipping from producer to consumer. A paragraph of text, an audio podcast, a video podcast, a Word document… If it can be put online, it can be shoved into a container (the RSS item), given a bill of lading (the RSS channel), pre-cleared for customs (tags, authors, keywords, etc.), and sent on its merry way on a conveyance (the RSS feed). Nobody has to touch the contents between shipper and receiver — just once to pack it, once to unpack it.

The feed is empty…. Fill it!

Addendum (10AM 5 August 08): Another similarity pointed out to me (thanks Cindi) is that RSS and shipping containers both lack security and authentication. The ramifications of this problem are a bit more serious for shipping containers than for feeds. Still, not really knowing who might have mucked with a feed between origin and destination, or having any real knowledge of who published it in the first place once the feed items are scattered around the Internet, can be a problem. Feeds, once set free, can have a life of their own.

New Pew Survey on Blogging and Blog Readership

The Pew Internet & American Life Project released a summary of a spring survey on bloggers and blog readers: New Numbers for Blogging and Blog Readership.

Although the full report is not presented, some summary information is. These points are of note in the report’s discussion about blog readership:

- “33% of internet users (the equivalent of 24% of all adults) say they read blogs, with 11% of internet users doing so on a typical day.”

- “42% of internet users (representing 32% of all adults)” say they have, at some time, read a blog or online journal.

- Men and women in this study are equally likely to say that they currently read other people’s blogs (35% for men, 32% for women)

- Men are more likely than women to say that they have read other people’s blogs at some point in the past (48% vs. 38%). Pew speculates that this difference is because men “are generally heavily represented among the early adopters for most technologies, but women catch up over time.”

Items of note in the discussion about blog authorship:

- “12% of internet users (representing 9% of all adults) say they ever create or work on their own online journal or blog.”

- “For a majority of bloggers, working on their blog is not an every-day activity: 5% of internet users blog on a typical day.”

If a quarter of all adults say they read blogs on a daily basis, I wonder what additional percentage read blogs without knowing it? I also wonder what percentage of the currently active blog-reading population does so via RSS, and if they realize they’re reading a blog when they go to Google Reader or Bloglines.

New Google Wannabe: Cuil

A new search engine created by ex-Googlers went public today: Cuil, pronounced, the site tells us, “cool;” it’s the Gaelic for “knowledge.” (And “hazel,” which seems less relevant.) The site seems to be suffering a bit from newcomer’s paralysis — the info page is currently not loading and some searches are timing out. Cuil claims to have indexed 120 billion pages, more than Google (which knows about over a trillion, but only indexes a small portion — though just how small, or large, Google’s not saying).

At first blush, I like Cuil’s layout. It presents results in two or three columns (you decide). Many results come with a small thumbnail image. In some cases, though, the image was of questionable relationship to the search; images were not present on the page you link to in a few cases. How images are applied is a mystery to me.

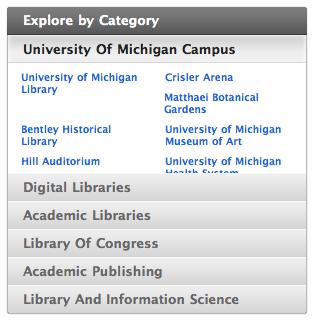

A search for “"University of Michigan Library"” (a phrase, including the quotes) finds it. It also presents “categories” of results on the right, with nicely bundled results.

However, its currency is a bit poor, at least for low-traffic sites like RSS4Lib. A search at Cuil for RSS4Lib pulls up the main page as the first result, but the text shown dates from October 2007, quite a few posts ago).

There’s no apparent way to save a search alert (by email or RSS), which is unfortunate, as that seems to me to be just part of doing business. The interface, though, is quite clean and (at least for now) free of advertising. I’ll be curious to see how this new search tool develops.

For those of you who enjoying poring through your servers log files, Cuil is powered by the “twiceler” crawler you may noticed going through your site.

Search Flickr for Color Schemes

The Multicolr Search Lab site lets you search through 3 million Flickr images for those that match a particular color. You can pick one or more colors from a swatch on that web page and it will display Flickr image thumbnails that contain the color (or colors) you pick. Assuming the photographer allows use of the images, you could use them to jazz up your web site with color-coordinated graphics. Of course, you still need to find one that suits your content.

If you’re not satisfied with the 144 colors offered, you can easily customize the tool to add the exact colors on your web page. For example, RSS4Lib uses three main colors: orange (#f1671f), dark blue-gray (#a3b8cc), and light blue-gray (#e6e2f2). By adding these to the site’s URL, as in this sample, I can get a customized set of images that match RSS4Lib’s color scheme.

This was generated from the following URL:

http://labs.ideeinc.com/multicolr/#colors=f1671f,a3b8cc,e6e2f2;

If you wanted to use your own colors, simply replace the 6-character color codes (in my example, the bolded f1671f, a3b8cc, and e6e2f2) with the colors you want to use. Add more by separating them with commas (no spaces!). End the list of colors with a semicolon.